Seventeen left-wing lawmakers have quit President Emmanuel Macron’s party in France and started their own group, called Ecology, Democracy and Solidarity.

The defections have deprived Macron of his absolute majority in the National Assembly. His La République En Marche is down to 288 out of 577 seats, although it still has the support of the centrist Democratic Movement (46 seats) and the center-right Agir (9).

The defectors accuse Macron of shifting to the right and neglecting income inequality and climate change.

That has more to do with perception than reality.

Balanced

The French left has denounced Macron as a “neoliberal” and “president of the rich” from the start, and hasn’t changed its rhetoric no matter what he’s done.

Yet his policies have balanced the interests of companies and workers, the private and public sectors, and the economy and the environment.

Macron abolished a largely symbolic wealth tax and reformed payroll taxes in a way that left the lowest incomes somewhat worse off. But he is also raising welfare benefits and extending them to a million more households.

Public spending still accounts for 56 percent of economic output, higher than in any other European country. France is one of only five countries in the developed world where income inequality and poverty have declined (PDF) in the last two decades.

Macron liberalized labor law to make it easier for companies to hire and fire workers, and eased regulations on small and medium-sized businesses.

But he also reined in labor migration from Eastern Europe to protect low-skilled workers in France, extended unemployment insurance to the self-employed and penalized companies for making excessive use of short-term contracts.

Macron allowed buses to compete with rail and ended automatic pay rises and early retirement at the state railway company. This angered the unions, but it cut prices for commuters.

Pension reforms will force workers in the public sector to work longer, but the changes will be phased in over decades and make the system fairer for workers in the private sector, especially women who interrupt their careers to raise children. They now typically work until 67 while most men retire at 60.

Under Macron’s health plan, dental services, eyeglasses and hearing aids will be free next year. He has cut classroom sizes in elementary schools in half.

Macron has kept climate change at the top of the international agenda and it was a fuel tax that gave him the biggest headache of his presidency: the Yellow Vests protests.

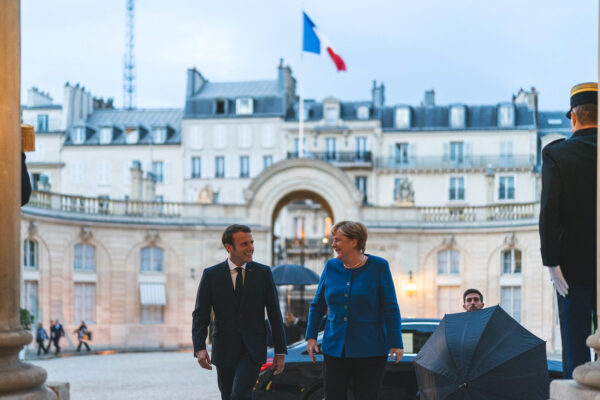

French greenhouse gas emissions are down and investments in a “European Green Deal” would be prioritized under the €500 billion coronavirus recovery fund Macron and German chancellor Angela Merkel proposed on Tuesday.

Introspection

Some leftwingers will never be satisfied. Others are still smarting over Macron’s own defection from the once-mighty Socialist Party, which collapsed in the 2017 election.

Rather than blame Macron, they should study their own failures.

The Socialists lost power after five years of unconvincing policy under François Hollande, who went back and forth between listening to Macron, who was his economy minister, and the trade unions. They picked the little-known left-wing purist Benoît Hamon, rather than the widely respected prime minister, Manuel Valls, as their presidential candidate; kicked Valls out when he backed Macron and called him a “traitor” and a “saboteur”; and competed with the far left rather than the center by calling for a universal basic income and higher taxes.

This Corbynist lurch to the left had a predictable (and predicted) result: Hamon placed fifth in the first round of the presidential election with a mere 6 percent of the votes. In legislative elections a month later, the Socialists went down from 41 to 7.5 percent support and lost 286 of their 331 seats in the National Assembly.

The far left did better but hardly demonstrated it could appeal to a broad segment of the electorate. Jean-Luc Mélenchon won 20 percent support in the presidential election, placing fourth, but his party won only 11 percent in the first voting round of the legislative elections and 5 percent in the second round, ending with seventeen seats, up from ten.

The numbers suggest around one in four French voters could support an uncompromising left-wing program. That’s not enough for Macron, who has wisely tried to unite the center-left and center-right against the far right of Marine Le Pen.