It’s worth asking how expensive nationalizing health insurance in the United States would be. I’ve told you before that cost estimates range from 13 to 21 percent of GDP, a difference of $1.7 trillion, or two-and-a-half times the Pentagon budget.

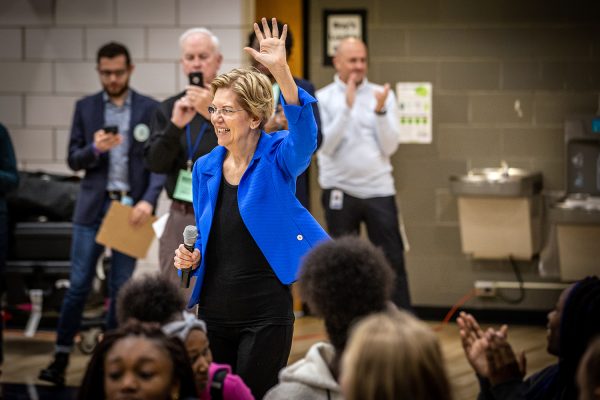

Senator Elizabeth Warren puts her plan at the low end of spectrum, about $2 trillion per year (which would still mean a 50-percent increase in federal spending). Even journalists broadly sympathetic to Medicare-for-all doubt that’s realistic.

I doubt it’s going to convince anyone. Medicare-for-all’s proponents are unlikely to change their minds even if they find out the cost isn’t manageable. Americans who oppose nationalizing health insurance are unlikely to come around even if it is.

The questions most Americans will be asking are:

- Would I pay more or less under Medicare-for-all?

- Would my health care get better or worse?

Who knows?

It’s impossible to answer those questions definitively.

Neither Warren nor Senator Bernie Sanders, who first proposed Medicare-for-all, has released a detailed tax plan (yet). They have released health care plans, but those are unlikely to be implemented.

Even if Democrats win the 2020 election, and even if they overcome strong institutional opposition to what would be the biggest change in health care since the introduction of Medicaid and Medicare in the 1960s, no president has yet seen a campaign plan enacted word-for-word by Congress.

This uncertainty, I’ve argued, calls into the question the wisdom of doing it at all.

But we can make some educated guesses.

Cost to consumers

Sanders and Warren insist that most Americans would, on balance, be better off.

Financially, that may be true. The average cost of an employer-sponsored health insurance plan this year is $20,576, up from $13,375 a decade ago. (And the percentage of workers with a deductible of $2,000 or more has gone up from 7 to 28 percent in the same period.)

A President Sanders or a President Warren would not want to raise taxes on middle and low incomes by an equivalent amount. More likely, they would raise taxes on high earners.

But who would be considered a high earner? And by how much would their taxes go up?

Action, reaction

Another unknown is how what remains of the private health-care industry would react.

Would all doctors and hospitals remain in business when they are reimbursed less under a Sanders or a Warren Administrations than they are by private insurers? Would all drug companies and manufacturers of medical devices remain in the United States if their patents expire? Would Americans put the exact same demand on the health care system as they do now and not seek more care if they can get it for “free”?

Sanders and Warren claim to think so. I doubt it, and so do many health care experts. Isn’t it more likely that some doctors would quit? That some hospitals would close? That some drug companies would move overseas and demand for health care would rise?

If that is the case, then either overall costs would be higher than Warren and Sanders project, necessitating higher taxes or larger deficits — or health care would need to be rationed.

Decisions

“Rationing” has been used as a scare tactic by the right, but it is an inevitable component of nationalized health care.

At the relatively benign end of the scale, it means doctors and hospitals are not reimbursed for using the most expensive version of a drug, incentivizing them to prescribe cheaper alternatives.

But the more you want to cut costs, the more you get into intimate and even life-and-death decisions. Should patients be able to go to any doctor and any hospital? Should expensive and experimental treatments be reimbursed when they haven’t yet proven to be life-saving? Do Democrats want a future Republican administration to make those decisions for 327 million Americans?

The American health care system is far from perfect, but one advantage of private insurance is that, at least in theory, consumers can make such decisions for themselves.

Finding a balance

The American system scores relatively high on outcomes. Those who have decent health insurance tend to get good health care. Americans suffer fewer post-operative complications than other Westerners. Cancer survival rates are high. Infant mortality is low. (Americans aren’t healthier than other Westerners, but that has more to do with their lifestyle.)

The problem, of course, is that not everyone has decent health insurance. Close to thirty million Americans are uninsured and millions more are underinsured.

Even Americans who think they have a good plan pay high copayments and deductibles and sometimes discover that a certain treatment isn’t covered or isn’t covered long-term.

America is the only rich country that lets people go bankrupt when they can’t pay their medical bills. There is a need for reform.

But there is a balance between availability of treatments and cost on the one hand and outcomes and waiting times on the other.

Americans have so far been willing to pay more (double the rich-country average, in fact) for the best possible care and short waiting times. If you want to improve accessibility and affordability, it will come at the expense of those things.

Mixed systems

Canada and the United Kingdom are examples of countries that prioritize accessibility and affordability. Both have more or less the same health care system, yet they perform very differently. Canada’s is on balance on the best health care systems in the developed world. Britain’s is one of the worst.

Looking at the developed world as a whole, Canada, not Britain, is the outlier. Generally, mixed public-private systems do best, because they find a balance between availability of treatments, cost, outcomes and waiting times.

I’ve argued before that Democrats should campaign for Dutch- rather British-style health reforms, and I will again.

The Netherlands moved away from single-payer in the early 2000s to expand the role of private insurance and private ownership in health care. The centerpiece reform was the introduction of an individual insurance mandate, which the Dutch borrowed from a right-wing think tank in America, the Heritage Foundation (which disowned its own idea two decades later, when Barack Obama adopted it).

The Dutch can choose from a variety of private insurance plans, as long as they get basic coverage. Insurers cannot refuse anyone. The government sets maximum prices for drugs and a maximum yearly copay, which is equivalent to about three months’ worth of premiums. Premiums pay half the actual cost of insurance. The other half is paid from payroll taxes. There are subsidies to help low incomes pay the first half. Insurers negotiate prices with doctors and hospitals and they can charge a premium for care provided outside their network. In most cases, doctors and hospitals will send their bills directly to the insurance company. Patients see little paperwork.

The Swiss system is similar and it’s no coincidence that the two are the best (PDF) in Europe.

Piecemeal

Gradualism has fallen out of favor on the American left, but a piecemeal approach is still advisable when reforming a $3.5 trillion industry that literally affects every single American.

I would start with severing the link between employment and health care, so Americans don’t lose their insurance when they are fired or stay in a job they don’t like because they need the insurance.

High drug prices are another low-hanging fruit. Americans pay more for medication than anyone else. The government could regulate price caps and pay the rest, and raise taxes on pharmaceutical companies to make up the difference.

Same with copays and deductibles; like the Dutch, Americans could set maximum prices on both. That would cause higher premiums, which could be offset by raising the income threshold under which Americans qualify for Obamacare subsidies. In the Netherlands, almost 60 percent of households receive some subsidy, the size of which is determined by income and the number of children.

You could go so far as to provide a public option: allow Americans to buy into Medicare. That is what presidential candidates Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg argue for, calling it “Medicare for all who want it”. Polls suggest that’s popular whereas forcing all Americans on Medicare is not.

All of these policies would require higher taxes too, but not in the astronomical range Sanders and Warren are thinking of. Nor would they take competition out of the health care system altogether, which is what the Dutch and Swiss believe is crucial to containing costs and ensuring good outcomes.