Replacing private health insurance with a single-payer, government-run system is hugely unpopular in the United States, but that hasn’t convinced two of the Democrats’ three top-polling presidential candidates — Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — to back away from it.

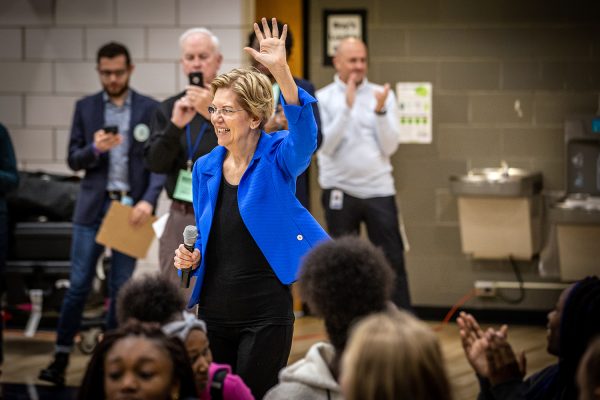

In the most recent televised debate, Warren, who is polling neck and neck with former vice president Joe Biden, couldn’t say how much “Medicare-for-all” would cost or who would pay for it. She has since promised to release a detailed plan.

Sanders, to his credit, admitted it would require tax increases. But by how much, and for whom, he didn’t say.

He can’t. Nationalizing health insurance for 327 million Americans is such a huge and complex undertaking that nobody knows how much it would cost.

Which calls into question the wisdom of doing it at all.

Uncertainties

The New York Times reports that total health care spending under Medicare-for-all could be anywhere between 13 and 21 percent of GDP, depending on whom you ask. That’s a difference of $1.7 trillion!

Health care currently accounts for 18 percent of the American economy, or $3.5 trillion.

If the federal government took over the whole system, wouldn’t the cost be the same?

No, because there are two uncertainties:

- How much Medicare-for-all would pay doctors and hospitals.

- How much demand for health care would increase.

How much to pay

Medicare, which currently covers medical care for seniors, pays health providers less than private insurers, which is why some doctors and clinics refuse to treat Medicare patients.

Setting the right rate is tricky. As The New York Times puts it:

Pay too little and you risk hospital closings and unhappy health care providers. Pay too much and the system will become far more expensive.

Which is why, in most cases, we prefer to leave such price-setting to the market.

You don’t shop for health care like you shop for groceries, but that doesn’t mean it is immune from the laws of supply and demand.

Most other rich countries regulate the cost of health care, but with minimum or maximum prices or within a certain band. Few set a single price for every drug and procedure, yet that is the system Medicare-for-all’s proponents want to go (back) to.

In their defense, Americans pay more for medication than anyone else. A single-payer system should be able to negotiate lower prices with drug companies and manufacturers of medical devices. But that could mean expensive drugs and procedures would no longer be available, at least not for free, as is indeed the case in countries with national health care.

If the goal is to lower drug prices, Medicare-for-all is overkill. Legislate a ceiling on drug prices instead and have either manufacturers or the government make up the difference.

Demand

Medicare-for-all would give insurance to 28 million Americans who currently don’t have any.

It would probably also cause Americans who did have health insurance before it to demand more care. If they have high copays or deductibles now, they might think twice before going to the doctor. Under Medicare-for-all, they wouldn’t have to.

But it is impossible to know how much demand would rise. Estimates range from 7 to 15 percent — a difference of hundreds of billions of dollars per year. For scale, the entire Pentagon budget is $686 billion.

Bureaucracy

An argument in favor of single-payer is that it would eliminate many administrative costs. Insurance companies spend money on claims review, marketing, negotiations and sometimes shareholder returns.

But the savings would in no way offset the projected increases. At best, it would shave 6 percent off total health care spending. Other estimates put the savings as low as 2 percent.

Who will pay?

Sanders and Warren insist that most Americans would, on balance, be better off.

Financially, that may be true. The average cost of an employer-sponsored health insurance plan this year is $20,576, up from $13,375 a decade ago. (And the percentage of workers with a deductible of $2,000 or more has gone up from 7 to 28 percent in the same period.)

A President Sanders or a President Warren would not want to raise taxes on middle and low incomes by an equivalent amount. More likely, they would propose to raise taxes for high earners.

But who would be considered a high earner? And by how much would their taxes go up? We don’t know, because neither Sanders nor Warren has released a detailed tax plan. (Even if they did, no presidential campaign plan is ever turned into law. At best, it would give Congress a starting point to write the necessary laws.)

Better health care

Then there’s the non-financial component. Would Medicare-for-all give Americans better health care?

There are so many variables and uncertainties that it’s impossible to answer definitively for the entire population. But I would point out that government-run systems, like Britain’s and Canada’s, tend to do worse, in terms of availability of treatments, cost, outcomes and waiting times, than mixed systems, such as the Netherlands’ and Switzerland’s.

The Netherlands actually moved away from a single-payer system in the early 2000s to expand the role of private insurance and private ownership in health care. The centerpiece reform was the introduction of an individual insurance mandate, which the Dutch borrowed from a right-wing think tank in America, the Heritage Foundation (which disowned its own idea two decades later, when Barack Obama adopted it).

Obamacare, in turn, again looked to countries like the Netherlands for inspiration. Today’s Democrats should do the same.

The choice isn’t between Medicare-for-all and the status quo. There are many options in between: options that would be cheaper, possibly better, and definitively more popular.