French president Emmanuel Macron has won a comfortable majority for his centrist party, La République En Marche!, but low turnout points to the difficult task ahead: convincing the less prosperous half of France to give him a chance.

An estimated 43 percent of voters turned out in the second round of parliamentary elections on Sunday, an historic low.

Macron’s victory was in little doubt, which may be why so many left- and right-wing voters chose to stay home.

The once-mighty Socialist and Republican parties were decimated. They are projected to win 49 and 125 out of 577 seats, respectively, against 355 for Macron.

The far left and far right lack the mass appeal needed to prevail in France’s two-round voting system.

Old parties collapse

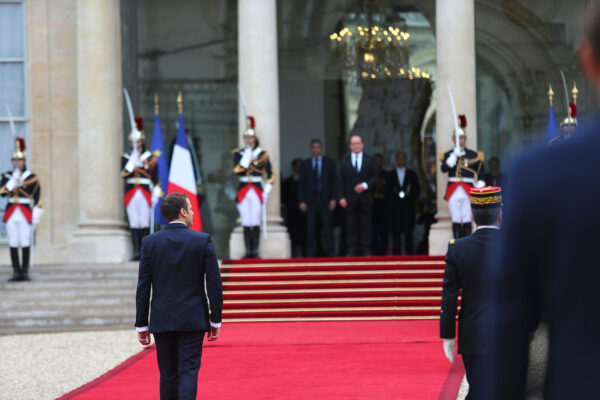

The old parties collapsed in the presidential election that brought Macron to power a month ago.

Neither the Socialist candidate, Benoît Hamon, nor the Republican, François Fillon, qualified for the runoff.

Macron drew most of his support from college graduates in the major cities and the prosperous west of France.

Marine Le Pen, the leader of the nativist National Front, placed a distant second overall but won constituencies in the economically depressed north of the country as well as its socially conservative southeast.

New cleavages emerge

Education, income and voters’ confidence in the future were the main cleavages.

Recent elections in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States have revealed similar splits.

This is what the Atlantic Sentinel calls Europe’s “blue-red” culture war over modernity — and it is replacing the old left-right division in politics.

“Blue” voters are cosmopolitan, university-educated, mostly urban and generally optimistic.

“Red” voters are less worldly, live in small towns or the countryside and feel their country is slipping away from them.

Macron’s challenge

Macron’s challenge is convincing “red” voters that the solution cannot be to pull up the drawbridges and pretend the modern world doesn’t exist out there.

Many have legitimate grievances, even if they didn’t vote this weekend. Industries have gone. Opportunity has been concentrated in the biggest cities. A college degree has become a passport to prosperity while vocational training has been neglected. These voters feel forgotten by the center.

But the French don’t have it so bad either.

The Financial Times points out that they still have world-class companies, well-run public services and generally comfortable living standards.

Social mobility is higher in France than in that supposed meritocracy, the United States.

And for all its integration challenges, France — unlike its European neighbors — has a strong civic ideal around which to unite people of all stripes.

Macron must tap into those strengths to boost France’s competitiveness, create opportunities for its unemployed youth and restore the country’s confidence about its place in the world.

After today, he can’t claim to lack a mandate for change.