There will be few who will miss 2016; perhaps fewer still that will miss 2017. Americans despair their electoral choices (choosing cancer or a heart attack, to some). Brits have quit the European Union. Turkey, post-coup, is also mid-purge. Islamic State’s lone wolves butcher and bomb. Even the pope is using the “w” word to describe the state of planetary affairs.

Yet if we step back, draw our heads out of the bleeding and leading trenches of 24/7 news and glance upon the supposedly pock-marked battlefield of our world, we see not vast burned out cities or massed firestorms sweeping upon us. The picture is much better than they say.

Here’s why.

Firstly, the world’s geopolitical system is not nearly as chaotic as it seems

It can very much look that way; Russia annexed Crimea, for God’s sake. Iraq and Syria have failed so badly as to give rise to the mad caliphate of the Islamic State. It isn’t hard to connect a handful of dots and smell the Apocalypse.

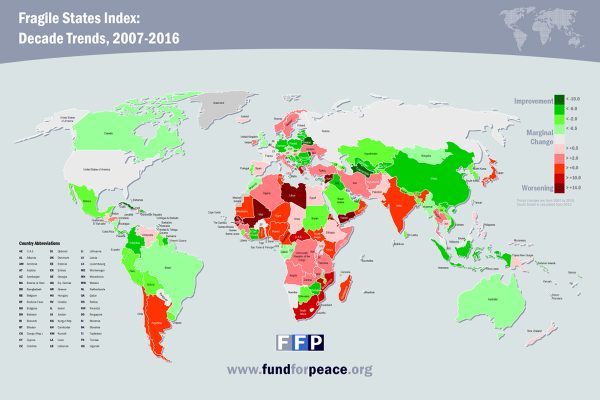

But that misses a greener, wider picture. Take a look below.

When it comes to regional and global peace, the key players are either as solid as they were in 2007 or better off; the United States guarantees North American security (and rogue states like Cuba have enjoyed boons in stability in the past ten years). In Europe, key American allies like Poland, Germany and Britain are all more stable now than they were in 2007; anchored by American power, Europe is as stable as ever. Only Ukraine has slid, where Putin’s hyper-local hybrid war has remained at a controlled geopolitical burn.

In South America, the worsening economic situation in Argentina and Chile is offset by security gains in Colombia (where the FARC has embarked upon peace), Peru and Bolivia while Brazil, messy though it is, has increasingly functional institutions.

While this map doesn’t reflect fully the slide of Venezuela, civil society remains functioning there, with President Nicolás Maduro threatened by a movement to recall him.

Asia, centered on Russia, Japan/South Korea/the United States, China and India has strongly positive results: Japan’s relative slide is due to its inability to find a new economic model to propel growth in the face of an aging population rather than an upsurge in some neo-imperial movement seeking to restore lost empire. India is in no danger of collapse; dysfunction is rife, but is not impossible to overcome.

Thus we focus on the usual suspects of geopolitical chaos: the litany of bad news from Africa and the Middle East. There are bright spots in Africa; Botswana and Zimbabwe both had low bars to overcome, but they are moving in the right direction while strong states like South Africa are moving away from stability. Libya’s and Mali’s collapses are well-known; yet go back thirty years and you’d find Chad, Ethiopia and Angola to replace them as basket cases. Africa may not be doing well, but it has certainly not become measurably worse.

Thus much of the perception of chaos comes from our media’s laser-like focus on the Middle East.

There is, to be fair, much to warrant that: the Middle East is much worse off than thirty years ago, with two major failed states (Yemen and Syria), one tottering (Iraq) and several future could-bes (Saudi Arabia, Oman, Jordan, Lebanon). Yet the Middle East is not central to the world’s economy or security system. Its energy supplies are not as critical as they once were; fracking and green energy are replacing sweet light Arabian crude. The communist threat has vanished; only the disorganized, near-suicidal Sunni supremacists pose a threat, but they hold no major industrialized bases and are not capable of fielding anything beyond militias.

Nor do Sunni supremacists seem likely to do so anytime soon. Should they conquer Iraq and Syria — the current strategy — they will still lack the capabilities needed to conquer further afield. They will run up against the places that are naturally superior — Turkey and Iran — as well as those that are artificially so (via Western largesse) — Israel and Saudi Arabia. Only when Iraq and Syria were armed by the Cold War were they capable of projecting power beyond their borders; there is no state that will arm the Sunni supremacists who seek to build their caliphate from them.

Meanwhile, key pillars of the world’s security system are in place and work just as they intend to

This isn’t to say they’re perfect; they’re not. But they do a fine job of being functional for their intentions.

NATO is meant to keep Germany down, Russia out and America in, in order to ensure that Europe does not repeat its oft-wretched past. For that purpose, it is doing a great job: the Russians menace, but they dare not move against NATO allies in the Baltics.

The US Pacific alliance system isn’t as formal, but is doing the same sort of task: keeping the Japanese down, the Chinese out and the Americans in. The Chinese are trying elaborate tricks like island building to get around this alliance wall built about them. There are abundant sign that isn’t working.

Combined, these two systems secure the Atlantic and Pacific from major war.

The United Nations, meanwhile, is a largely symbolic and often ineffective institution meant to defuse tensions between the major powers. It does just that, forcing the Russians, Chinese, Americans and others to tables they would otherwise not be at. The UN was not designed to create world peace, but to prevent World War III. It has achieved that aim, even if has fiddled while countries like Syria burn.

Meanwhile, from an ideological perspective, there is hardly any competition to capitalism: most systems are racing toward it rather than away from it. Only Sunni supremacism somewhat challenges it, but even it dares not reach as far as the Soviets in trying to rewrite economics.

But while World War III is quite distant, what then about the threat of terrorism?

There are indications that that too is overblown, at least in much of the world.

The United States went from 2002 until 2015 without a major Sunni supremacist terror attack, when the San Bernardino mass shooting broke the long peace. That too might have been labeled as crime rather than terrorism had the shooter not, at the last minute, pledged allegiance to the Islamic State.

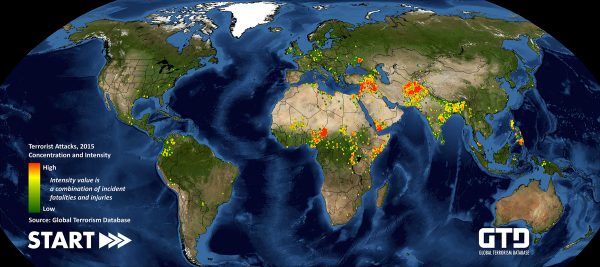

This map below, created by the Global Terrorism Database, shows terror attacks in 2015. They are hyperlocalized and mostly predictable: Syria, Nigeria, Iraq and Afghanistan glow, while Europe and the Americas appear tranquil. (For further delving, check out their amazing historical terror infographic, which allows you to track the victims of various terror groups going back to the 1970s.)

The database reveals more: When you remove the hotspots of Southwest Asia, South Asia (which includes Afghanistan) and Sub-Saharan Africa, it emerges that the 1980s, not today, were the decade of terror for much of the world. But print journalism could never propel such terrorism to the same heights of 24/7 cable news.

But there is other, rosier news: everyone’s economy is still growing

Despite the Great Recession; despite the hoarding of wealth by the top elites; despite the drumbeat of bad economic news and stock market crashes, everyone is still better off than they were in 1990. Wartorn zones aside, the world’s economy continues to lurch forward. There are troubling indicators that say China’s economic miracle may be coming to a close, but that is not necessarily doomsday, nor should we treat it as such.

Rather than face yet another recession, the global economy continues to grow upwards of 3 percent per year, even with major countries like Japan stagnating and the EU zone wobbling.

Finally, there is the great crime drop

Your guess on this is one is as good as mine, but stats don’t lie: we are all safer from crime than we were in 1990.

There are varying theories: removing lead from paint and gasoline made folks less violent, the drug epidemic has subsided, poverty is no longer as extreme, major cities that were grappling with deindustrialization have finished their work and become knowledge cities. But you are far less likely today in the West to be mugged, murdered, assaulted, robbed or raped than you have been since the 1950s.

So then why don’t we feel like everything is okay?

There are competing reasons. First, during economic crises, people focus more on survival as they see it than on wider social issues. This forces pragmatism rather than conflict on many. The Great Recession forced issues like the culture wars aside for a few years while people scrambled to find work.

Second, societies take time to adjust to new realities. The murderous 1980s and 90s were not so long ago that the myths that arose from them have been put to rest. Consider how many Americans might still think Iran sponsors Al Qaeda; a 1980s assumption stemming from the hostage crisis of 1979-91. Consider as well how many urban myths are based upon the great crime wave of 1965-96: flashing your lights is a signal to get shot, New York City is a dangerous place, etc. (New York is the safest big city in America while as recently as 1990 over 2,000 people were murdered a year.)

But thirdly, and most importantly, the West is now embarking upon a final generational and societal shift that’s been in the making since the 1960s. Consider now that the hippies of yesteryear are grey and facing mortality. They and those who despised them amongst their peers are fighting the last gasps of the culture wars.

This isn’t restricted to America; Parisian students rioted in 1968 just as much as New Yorkers did. For the children born in the late 1940s and 50s (baby boomers in America), who avoided World War II and who have spent much of their lives seeking authenticity, creativity and morality (and who have found it in such disparate forms as hippie sex communes and Baptist Bible churches), their lives are now coming to their final phase.

As they still have energy to organize politically for one final push, they are drawing battlelines and hyping up their struggle in the media and in politics. Some coalesce around white nationalists like Donald Trump, France’s Marie LePen and UKIP’s Nigel Farange, fearing that when they die they will give over their country to a people and culture completely unlike them.

Their opponents seek legacy as well. They gather about the likes of Hillary Clinton, seeking the post-racial society they believe they began in the civil rights movement of the 1960s. They have accomplished much: gay marriage, drug normalization and gender equality. But they have failed as well: old-fashioned racism, mass shootings and defeating Sunni supremacism.

It is these forces who propel forward the notion that things have never been worse. For some folks, this is true. What they cared about most of their lives is becoming irrelevant as new generations replace them in offices, schools and government. As boisterous, loud and ostentatious as they were in their protests of the 1960s, as unpredictable as they were as they committed the great crime surge, they now are carrying out last-minute political projects through the media they still largely control and through the political parties they now dominate.

There is theory on how this will all end: William Strauss and Neil Howe wrote as much in their book, The 4th Turning. The reactionaries will win tactical victories but strategic defeats: they cannot manage the twenty-first century by pretending it is the twentieth, especially as they grow grey and feeble. Their message hardly resonates with their children and grandchildren, who have no fond memories of the 1950s.

It will fall to the progressives to manage the transition. We already know much of what that world will look like: gender, sexual and racial equality will be considered a given, even if imperfectly applied. But questions remain: What to do in the face of the implacable hatred of the Islamic State? How to manage authoritarian regimes like China and Russia who might upend the world? How to ensure that not only does everyone become richer but everyone feels richer as well? And how to survive, perhaps even thrive, in the face of imminent climate change?

These are questions the reactionaries cannot answer. They will try; they will invariably fail.

The final phase of our generational turnings is coming to a close. What is on the other side will not be perfect, but it will feel rather close to it.

This story first appeared at Geopolitics Made Super, July 27, 2016.